- Home

- Ana Maria Machado

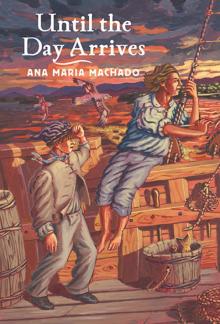

Until the Day Arrives

Until the Day Arrives Read online

UNTIL THE DAY ARRIVES

* * *

ANA MARIA MACHADO

TRANSLATED BY JANE SPRINGER

Groundwood Books

House of Anansi Press

Toronto / Berkeley

1

—

Bento

It was all very unexpected. All it took was an instant. In a few minutes, Bento’s life changed forever. And Manu’s life, too, although it wasn’t obvious at the time.

Manu saw the guards take Bento away. But all he could do was hide so as not to be seized as well.

It wasn’t clear how the brawl had started. But it soon became violent, ugly. Manu heard the shouting and saw Bento throw a plate of leftover food at someone. There was such an uproar that it was impossible to make out what was going on. He wanted to help, but he was too far away, coming down the stairs with a tray that the tavern’s owner had asked him to bring from one of the rooms.

Bottles were flying, barrels were rolling, dishes were breaking, creating a huge din. Some of the brawlers joined arms to overturn the heavy, long table that would seat ten men at the end of the day. In seconds, it was transformed into a barricade, protecting Bento and the innkeeper’s son.

“Call the king’s guards!” someone shouted.

Everyone in the city knew that this distress call would soon bring the soldiers of the king. They’d arrive in no time, aggressive and confrontational.

Manu stood on the stairs, tray in hand, stunned by the sudden violence. Bento signaled not to go down. Without actually hearing his words, Manu understood perfectly what he was saying, his hands cupped around his mouth.

“Get out of here! Don’t let them grab you!”

Manu stepped back and hid behind a huge chest on the landing that was used for storing mugs and tin plates. Afraid and angry at the same time, he wanted to run away and disappear, but also felt like jumping into the fray and swatting people left and right, or smashing someone with the tray. He didn’t know what to do, but obeyed Bento. His heart was pounding hard enough to burst.

From his hiding place he watched as someone evil-looking hit Bento on the head with a heavy object. A candlestick, maybe. Bento staggered. A trickle of blood began to drip down his forehead.

“Here come the guards! The guards!”

As the message spread, people ran in all directions. The place emptied in seconds. Only Bento was left standing in the immense room, half-dazed, disoriented, not really seeing straight. He swung and lumbered all over the place, and then he fell. Three pairs of arms grabbed him at the same time. They all belonged to soldiers of the guard.

He tried hard to defend himself.

“Let go of me! I didn’t do anything! Hurry, go after them! The guilty ones are going to escape!”

Bento was given a huge shove, while the soldier who seemed to be in charge answered him.

“What guilty ones? There’s nobody else here. Only you, and you’re going to stay tied up while the innkeeper serves us a good wine to thank us for restoring order.”

That was too much. Already angry, Bento became furious.

“There’s no one here because everyone has fled. Are you going to let them escape? Run after them! Hurry up, you cowards!”

One of the soldiers drew his sword menacingly. Two others bound Bento’s wrists with a rope and forced him to sit on the stairs. But this still didn’t silence the boy. Bloodied and angry, he continued to fight with words.

“Surely His Majesty doesn’t pay your wages so you can sip wine for free instead of chasing hoodlums!”

“We’re holding the only troublemaker we found — a troublemaker who can barely stand up he’s been drinking so much. Not to mention he’s nearly destroyed the workplace that supports a family. And now he’s incurred new crimes — disregarding the guards’ authority and even managing to insult His Majesty.”

Bento knew better than to continue to rant. It would only complicate his situation. It was better to remain silent.

Stammering with fear, the tavern owner tried to explain what had happened.

“He’s ri-i-i-ight, sirs. He’s t-t-telling the t-t-truth …”

The guard commander’s response was sharp.

“Don’t argue, man! Bring us our wine, right away. Or do you want us to take you in, too?”

Even though he was Bento’s boss, the innkeeper knew that he was helpless against this brutality. There was no use trying to explain anything.

Quietly sitting on the step, his wrists tied, his head aching and bleeding, Bento was beginning to understand the full extent of the danger he was in. But gripped by an older brother’s concern, he remembered his father’s advice. He was responsible. He couldn’t let anything bad happen to Manu.

Careful not to turn his head, he looked through the wooden banister and spotted the small figure crouching behind the chest. He did what he could. Pretending to scratch his face, he raised his tied hands and held his right index finger in front of his mouth. It was an eloquent plea for silence. A silent piece of brotherly advice and protection.

His guidance was understood and followed. Wavering between wanting to run off and a rash desire to attack the guards, the hidden figure shrank a little into the shadows. It was from there that Manu watched the soldiers take Bento away. Where, he didn’t know, but he would find out. Even if it meant searching all over Lisbon.

2

—

Manu

Manu was exhausted and hungry — very hungry. A little cold, too. He needed to get something to eat and find a place to spend the night that was sheltered from the wind.

The past few days had been difficult, the day before particularly upsetting. Things had improved when Manu came to Lisbon with Bento, but recently everything had turned bad again. Very bad.

At first, right after the fight and Bento’s arrest, Manu managed to stay at the tavern, working hard — helping to serve tables, carrying water, washing dishes, sweeping the floor. In return, he had enough to eat and a place to sleep. There was more work now that Bento wasn’t there. The innkeeper and his wife agreed to let Manu continue because they needed help, even if it was a child’s help.

“A kid’s work is only a trifle, but anyone who doesn’t take advantage of it is crazy,” the boss would always say.

And his wife would sometimes acknowledge in a protective tone, “The kid works hard.”

The nickname stuck. It was kid here, kid there. No one was interested in knowing his real name.

“Kid, go fetch a pail of water from the well there.”

“Take this to that table, kid. But be careful, it’s hot!”

Heavy or not, Manu carried it, taking small steps, sometimes stumbling. He did what was possible, being slight and not yet twelve. The child followed every order, more than ever now that Bento was gone.

Desperate to find out where Bento was, Manu struggled to overhear conversations while serving tables. But the subject never came up. No one seemed to remember what had happened. Finally, Manu drummed up the courage to ask the innkeeper’s wife.

“Where did they take my brother?”

“To jail, of course. Where did you think he would be? He’s probably been flung into a dungeon by now.”

This was very vague. Manu persisted.

“And where is this dungeon?”

“I don’t know.”

“How can we find out?”

The woman looked admiringly at the dirty little face, with its delicate lines and bright, curious expression.

“I have no idea, but I can ask my husband.”

A

nd she continued to scald the freshly slaughtered chicken she was using to prepare soup.

A while later, when the innkeeper came into the kitchen, Manu reminded her, “Don’t forget to ask him, please?”

“Ask what?”

“Where the dungeon is …”

The woman turned to look at the child and took pity. She faced her husband.

“Tavares, do you know where they took Bento?”

“To prison, of course.”

Manu could not help asking, “Where is this prison? And what will they do with him?”

“I don’t know. You never know. But there’s usually a stiff penalty in such cases. It wasn’t just a fight — he’s accused of insulting the king.”

“That’s not true,” Manu protested. “We all know that it isn’t true.”

“You think you can convince the guards? The judges?” said the man, smiling.

“I don’t know. But I can go there and explain what happened.”

The innkeepers laughed, thinking that kids just didn’t understand how the world worked. Just imagine, a child being allowed to enter a prison or a court and arguing with the authorities.

But Manu insisted, “Where is this prison? Where did they take Bento?”

The innkeeper carefully explained how to get to the gates of the building where he supposed the boy was locked up. But he added, “Don’t get into any more trouble. If you even go near there, don’t bother coming back. I don’t want those guards in my house again.”

And that’s how Manu lost his job. He took the boss’s words quite literally. Of course he went to the prison to try to rescue Bento — and afterwards never returned to the inn.

The rescue attempt was futile. Nobody could be bothered to listen to Manu, and they didn’t let him into the prison. It wasn’t even possible to find someone trustworthy to give Bento their father’s pocket knife. He might need it, being alone inside the dungeon.

Now Manu was wandering the hills of Lisbon, having eaten nothing for two days except a scrap of old bread a woman had given him the day before. His belly rumbled, his head ached and his vision was a little cloudy. Hunger seemed to make everything colder. Dark clouds were gathering in the sky, threatening rain, and thunder became increasingly frequent. The wind was icy with heavy moisture from the river, cutting Manu’s skin. He needed to find some shelter.

Turning a corner, Manu saw four or five people sitting on the side steps of a church. They were dressed in very old, worn clothes, some of them in rags. As he approached, the door of the sacristy opened. Everyone stood up.

“Did you also come for the soup?” asked the sexton.

“Yes,” Manu affirmed, hearing about the food.

“Every day there’s a new mouth,” was the response.

The sexton offered him a slice of bread and a bowl of hot liquid with chunks of cabbage and turnip floating in it. Manu ate heartily. When he returned the bowl, he asked the sexton if he could help with something in return for the meal. He offered to wash dishes or carry water.

“So take this bucket and bring me some water,” the man accepted, barely glancing in Manu’s direction. With a nod, he indicated a well that could be seen through a half-open door. It was in the inner courtyard of the cloister — a small garden, with orange trees and medicinal herbs, surrounded by galleries with archways that were supported by finely carved stone columns.

During his little foray into the courtyard, Manu noticed another partly open door that led into the church. It would be a sheltered place to spend the night, he thought. Leaving the bucket in the sacristy, he took advantage of the sexton looking the other way to slip inside.

It was a huge stone church, with an elevated nave full of columns. Perhaps during the day, when the sun was shining, some light seeped through the stained-glass windows way up there, close to the ceiling. But at that time, as the sun was going down, the church was very dark and a little daunting in its magnitude and solemnity. It resembled a large cave where wolves and bears would live. Everywhere, there were strange and menacing carved stone figures that seemed to have walked out of a nightmare. The church was frightening. But it was the house of God, Manu knew. And there was no rain or wind.

After a while, Manu heard the sexton’s footsteps. He drew back and ducked behind a low wall, then climbed a small spiral staircase and hid in the pulpit.

There was no need to worry. The man didn’t enter the church. He had just come to close the heavy door, which creaked loudly. He didn’t even glance inside. It didn’t enter his head that a child could be hiding within those walls.

And so Manu started sleeping in the house of God. It was cold, but it was protected from the elements, including the sudden bursts of lightning, which on that first night flashed through the windows, illuminating the stone figures and casting colorful shadows in ghostly corners.

Besides being a sheltered place, the church brought the prospect of hot broth every night. It also secured what may have been Manu’s only solace — the loving smile of a stone lady with a small boy on her lap. Our Lady, everyone said. Manu knew who she was and remembered how their mother used to pray to her, saying a Hail Mary with each bead of the rosary. Before their mother died, she had feebly asked the mother of Jesus to take care of her children who would be alone in the world.

That first night in the church — listening to the storm outside and wondering how to find Bento — Manu felt protected. He settled down to sleep at the top of some steps, right at the foot of Mary’s altar. Close by were the stubs of lit candles. In the weak and trembling light, Manu could see the strength in that maternal figure. It was as if his mother were still there, pushing sadness a little farther away and making him feel a little less alone.

3

—

Alone

Manu spent a few days wandering around the town and sleeping in the church at night, after doing dishes, carrying wood and fetching water for the sexton. There had been no contact with Bento. Manu had no idea how to get him out of prison. Force wasn’t an option, since Manu was weak and without resources. Tears and appeals were not going to work, either. Manu had already cried and begged in front of the guards, but was met only with cruelty, laughter and ridicule.

“Here comes the whiner again.”

“Get out of here, kid!”

“Nuisance!”

He hovered around like a silly, sluggish fly that insists on landing everywhere, until finally he would scarcely show up before the guards tried to get rid of him. They wouldn’t even let him linger near the gates as they had in the early days.

If only Manu could talk to Bento, surely he would be able to come up with a plan. His older brother was smart and full of ideas. If it hadn’t been for him, the two of them would still be in the village where they were born. Or they would have died of the plague, like the rest of their family and almost all their neighbors.

Just thinking about it made Manu’s eyes cloud up and almost overflow with tears. His head and heart were filled with sad memories of two younger brothers and their mother and father. They had all been sick in the small, dark house, and when they stopped clinging to life, their bodies were thrown on top of the pile that was growing at the front door. Then, one by one, they were taken away in the wagon used to carry the dead. It was done in a hurry, because there were so many bodies, and burials had to be quick to try to contain the plague that raged from street to street.

Manu would never forget the day they put their father’s body on the wagon, and the two of them were all alone. Bento made a decision.

“Father told me to look after you and take care of everything. Let’s get out of here.”

“Where should we go?”

“I don’t know. But staying means waiting for the plague to get us, too. We have to get away, right now. The whole town is sick, Manu. It’s only a matter of time.”

Time �

� trying to escape time. Moving away from an earlier time — a wonderful time, with family, their siblings’ playfulness, their mother’s lap and smile, their father’s voice telling stories by the fire at the end of the day. The time when Manu had a home.

All this had been left behind.

Within hours, they were on the road. They took only a few things — a change of clothes from one sibling, a coat inherited from another, their mother’s rosary, their father’s pocket knife. And a small object — the ceramic dove that Manu quickly snatched from a shelf and tucked in a pocket just before they left. It was so tiny and delicate, white and blue. Manu didn’t know if it was a toy or an ornament.

He remembered when it had been made. Their father had brought home a ball of clay from the workshop. It was wrapped in a damp cloth, and he showed the children how to shape it. All of them spent a Sunday playing with the clay, making models of animals — roosters, dogs and cats. None was as beautiful or as perfect as the small dove that emerged from their father’s deft fingers while he was teaching them. Manu would never forget their father’s long, magical hands, which were able to give life to wet earth.

The next day, Manu went with him to the workshop. Taking advantage of the hot kiln used to fire the dishes made by the pottery workers, he put the clay dove inside to fix the glaze. Manu saw how he had painted the dove with pigments that would change color with the heat of the kiln and turn the scratched lines representing the dove’s feathers blue. Later, when it came time to take everything out of the kiln, there it was amid all the pots and jars — a graceful blue-and-white glazed dove, tiny and perfect, ready to go back to their home. The dove lived on the shelf, looking as if it had just softly landed there to celebrate a day of peace and family joy. It watched over them all.

But the dove belonged to Manu. Forever after, he would remember the smile with which their father handed him the dove when it had cooled.

“Take it,” he said. “It’s for you.” And he patted Manu on the head with his long fingers.

Until the Day Arrives

Until the Day Arrives The History Mystery

The History Mystery